Chris would rather be anywhere but here, cleaning out his deceased, hateful grandparents’ house with his relatives. Each room he visits takes him back in time to another traumatic memory. To escape this house and his grandparents and his past, he’ll need to take time travel into his own hands.

Content warning for fictional depictions of verbal, physical, and sexual child abuse.

There was supposed to be a cameo somewhere in Birdie’s bedroom, but no one could find it. They’d gone through all the jewelry and keepsakes. All they’d found was her sapphire ring, loose in a cookie tin, along with a bundle of sepia photographs showing people crowded around the hotel that Birdie’s family had owned when she was a child during the Great Depression. Lily and Harold argued over the identities of the people in the pictures, but came to no consensus.

The cameo was a Civil War heirloom. Birdie had made a point of mentioning it whenever she talked to her children and grandchildren about their eventual inheritance.

Marian frowned at the empty closet. Could it have accidentally gotten packed with Dad’s suits in the bags for Goodwill?

Her twin, Lily, whipped toward her with an angry expression. She’d packed those bags. Is that an accusation?

Marian crossed her arms defensively. I’m not blaming anyone. I’m trying to figure out what happened.

I’m not stupid.

Buy the Book

Placed into Abyss (Mise en Abyse)

I didn’t say you were stupid.

Why don’t you drive to Goodwill and get the bags back if you’re so sure that’s where it is?

Marian rolled her eyes extravagantly. She turned to their older brother, Harold. Tell her she’s being crazy.

Harold opened his mouth, but failed to speak before being interrupted.

Lily ground her teeth. I’m being crazy?

I’m sick of both of you. Harold grabbed an armload of Birdie’s shirts from their hangers and slung them on the floor. I’m not missing my flight home on Monday. We need to get this done.

Chris stood in the corner, pressed against the armoire, wishing he could disappear into the nicotine-stained wallpaper so he wouldn’t have to hear his aunts and uncle arguing. He hunched his shoulders, trying to make himself too small and insignificant to be drawn into the fight.

The room was drowning in muggy summer heat, only vaguely stirred by the air conditioning. All six of them who had flown out to help pack the house were crammed inside. Chris hated the bedroom’s claustrophobic pressure—the looming, oversized furniture; the weird, weak light that penetrated the dirty glass of the ceiling lamp; the mud-brown curtains into which that light disappeared and mutated into shadow. It felt as though they were falling together into a black hole, time and space deforming around them as Lily, Marian, and Harold circled each other in unstable orbits.

Chris’s cousins, Pearl and Jim, sat on the edge of the bed, whispering to each other. They’d been smoking pot earlier, squatting in the herb garden and staring through the fence slats at the neighbor’s chickens, idly joking about breaking into the coop to steal dinner. Jim giggled. Pearl made eye contact with Chris and gestured for him to sit beside them on the dusty comforter, but Chris declined with a small headshake.

It’s ridiculous that we have to do the whole place at once. We should have gotten Birdie to let us pack up Dad’s stuff years ago. Harold threw down another armload. Where are the empty bags?

We ran out when we packed the last load. When I packed the last load. Lily’s lips pinched together. There might be more in the garage.

Chris mumbled that he’d go look for them. Harold gestured him toward the door without turning away from his sisters. Chris slid past Pearl and Jim, who ignored him, scrutinizing each other’s faces intensely as they played a hand-slapping game that Chris had never learned.

There was little light in the hallway apart from the murmur of yellow underneath the master bedroom door. The continuous cough of the air conditioner rattled vintage frames against the walls. In their black-and-white high school portraits, his twin aunts, Lily and Marian, regarded the camera with pouting lips, imitating movie stars. Harold looked disgruntled, unkempt hair falling in his face. Chris’s father, Trapper (who had broken his leg on a ski trip three weeks ago, which was why he hadn’t flown out to Buffalo to help with the house), wore a dreamy look, his head cocked to one side, his gaze aimed diffusely upward. It was always odd, looking at old pictures of his father from the days when he’d been beardless and firm-chinned, when his eyebrows had still grown straight instead of woolly.

The collages of Birdie’s grandkids were all in color, taken with varying equipment and skill. Some were bleached by too much light, others glaringly oversaturated. Pearl and Jim in a wading pool. Chris crying over a scraped knee after winning a soccer game. Pearl leaning out of a window at a historical park in Boston. Jim showing off a science fair ribbon. All of them smiling awkwardly next to their parents, and their aunts, and their uncles, in endless recombinations of pasted grins.

Chris blurred his gaze before it passed over the holiday photographs of his grandparents, who had posed together year after year in the same position, distinguished only by hairstyles, clothes, weight, and wrinkles. All he caught was Birdie’s silhouette in the leftmost one, her head tilted as she stared into her husband’s face. Beside her, the gloss of the glass transformed Grover into a burst of empty light. Chris rapidly turned away, his vision stippled with afterimages.

The hallway was T-shaped, with the left branch leading to the master bedroom, and the right branch to the old children’s bedrooms. As he took a step toward the perpendicular fork that led to the front of the house, a fathomless dread began to itch down his neck.

Behind him, he heard a knock coming from one of the back bedroom doors. It came from the right. To the left, Chris could still hear his family’s raised voices coming from the master bedroom. There was no one else in the house. The knock was a soft rap, as if testing to see if the person inside the room was awake. It made the door vibrate and the knob ring.

Chris’s stomach tightened. He felt suddenly as if he were very high up, and the hallway behind him had become a pit. Vertigo swept through him. He fell a few steps backward. The knock repeated, and this time he was close enough to distinguish the rattle of wood against the door frame. He braced himself against the wall, refusing to let himself plunge. The sense of gravity increased, wildly, angrily, before finally subsiding. He stood breathing heavily for a moment as up and down gradually returned to normal.

He continued through the hallway and emerged into the living room. He surveyed the last pieces of furniture that hadn’t been hauled away. The orange arm chair was broken, its footrest permanently canted at an uneasy angle. On the sofa table, an empty bowl sat next to its twin which held the wrappers from empty Hershey’s kisses.

There was the sound of a glass being set down, and Chris saw that two fingers of scotch now stood in a rock glass on the table, still mildly sloshing from being moved. The wall clock above chirped as it hit six o’clock, the hour when Birdie had begun closing the day with one drink, just one.

Rose-and-jasmine perfume fogged the air. If I were you, I wouldn’t have children either, said no one. The scotch began sloshing again as if the glass had been raised in a gesture. With your problems, you wouldn’t be doing them any favors.

Into the following pause, Chris did not murmur yeah so quietly that the sound barely colored his exhale.

Through an open window, evening breeze came in, smelling of buckwheat and autumn decay. No one gave a sharp cough, and then there were lipstick and fingerprints on the glass, and it was empty except for amber residue. Chris picked it up on his way into the kitchen. Lily and Marian would be furious if they thought someone had been drinking while the work wasn’t done, not knowing Pearl and Jim were surviving on smoking pot and drinking vodka in plastic water bottles.

At the breakfast table, Chris’s mother was laying out a game of Solitaire. She flipped the cards slickly, skilled from the year she’d spent in Atlantic City before marrying his dad. Don’t just stare at me, no one said. Sit down if you’re going to. Have you eaten breakfast yet?

The light coming through the window was high and emphatically yellow. Spring was opening the primroses.

Chris set the glass on the table, then grabbed a cereal bowl from the cabinet and a carton of whole milk from the fridge. On the table sat a box of Lucky Charms, the brand he’d insisted on eating from ages four to ten, and hadn’t touched since.

He sat across from his mother and shook out the cereal, then poured in the milk. She wasn’t paying him any attention. She’d found a burst of moves and was slapping down her cards.

Her hair was in the pixie cut she’d worn when Chris was little, until she’d started complaining that she’d gained too much weight in her face. Her hands were smooth, with no arthritis in the knuckles, and she was still wearing the modest wedding ring she’d returned to his dad after the divorce.

Where’s Dad? Chris didn’t ask in a piping voice.

No one replied, On the roof, checking to see if he can fix it himself or if we need to call someone.

I saw him crying this morning. The spoon was too big in Chris’s tiny, chubby fingers. He dug it into the cereal like a shovel, and forgot to chew with his mouth closed.

Mmhm. His mother’s expression was tight. She stared fixedly at the cards.

Chris didn’t ask, Why do we still come here?

Your grandparents need help.

So what?

His mother’s hand paused, hovering over the deck. She lifted her eyes, gently but firmly, to his. Your father wants to.

Sudden anger surged through him, and he couldn’t choke it back. So what! I don’t want to!

Chris’s throat tightened and he burst into tears. Snot ran disgustingly down his face. He banged his fists on the table, and the milk jostled, splashing out of the bowl. The Lucky Charms got soggy as he punched and sobbed, and then they were gone, and the spilled milk had disappeared, and so had the cereal box.

He put away the carton, which hadn’t disappeared, and put the bowl and glass in the dishwasher. Someone, probably Pearl, had left a pile of the good dishes in the sink, the ones that had to be washed by hand. There was no reason to do that except to aggravate everyone else; Pearl was like that when she got stressed out. He squirted dish soap onto a sponge.

The cupboard beside him swung open, the half-empty scotch bottle sitting alone on a low shelf. You shouldn’t feel bad that you can’t find a girlfriend, no one said. You’re just hard to like.

Chris continued scrubbing, but his hands had gone wrong again. They were the same size as they normally were, but his fingers were thin and knobbly, not yet fleshed out by adulthood. Hail rattled against the window. The plate fell and smashed.

You remind me of my sister’s kid, no one continued. There was a small sigh of reminiscence. God, that boy was annoying.

The cabinet slammed shut, and there were departing footsteps, and a lingering clot of rose perfume. A voice came from the breakfast table behind him. Don’t let it get to you. Just ignore her. Chris looked back, but his mother was no longer sitting there playing Solitaire; the table was empty, surrounded by lifeless chairs.

With hands that were adult again, he cleaned up the broken pieces of the plate and threw them away. He left the other plates in the sink where someone less stupid could finish them. Marian would probably yell at him about it. She yelled a lot when things were going wrong.

Chris passed through the kitchen into the garage. His shoulders slumped as he looked at the unsorted boxes piled next to his grandparents’ old car. There was so much left to do.

He took the box of trash bags off of the shelves that held the cleaning supplies and tools. The box was empty. He peered into it, then put it back on the shelf. Someone would have to get more—perhaps he could—but even as the thought formed, a nauseous feeling told him it would be impossible. In his skin, he could feel the pull of the house. It had him trapped. It wouldn’t let him go.

The engine of the old Camaro revved, and Chris felt sick again, unsurprised by the sensation of hands shoving him toward the car. Birdie’s perfume clouded around him as his body hit the door. He was the same height as the rearview mirror, and it clipped his ear.

He screamed and threw himself on the ground. His elbows smacked painfully against the cement, and he remembered the bruises he was about to get from hurling himself around, which had bloomed black and lasted until Valentine’s Day.

He didn’t say, I don’t want to go I don’t want to go I don’t want to go I don’t want to go.

He looked up at the distorted, tree-like limbs of his father and grandmother. His father’s face was clenched and pink. He hated how his son still raged like a toddler.

Christopher! Knock it off! No voice paused. No voice continued. I’m sorry he’s making a scene. I don’t know why he’s upset. He likes the library.

You can’t spoil children. You kids would never have done this when you were young.

Things are different these days.

That’s what they say.

A man’s hand dragged Chris upward by the shoulder. The car door groaned as his father pulled it open. Apologize to your grandfather.

Blinding light poured out of the car. Its searing color overloaded Chris’s vision, seeming to smolder with blue and then white and then purple as his eyes struggled to make sense of brightness beyond their ability to see. It was like staring into the sun—but a wrong sun, a sun he should never have encountered.

The hand prodded Chris. Apologize.

I’m so— I’m sorr— I’m—

Angry tears burned his throat, choking him with shame and fury and impotence. He couldn’t do anything, he could never do anything, it didn’t matter what he tried, he was a stupid kid and they’d ignore him. He sagged, and the tears stopped, leaving him with a sore throat and the feeling that everything in him had been hollowed out. He was disgusting. He should find a way to be someone else. But he’d tried before, and no matter how hard he tried to hammer himself down, the badness leaked out.

I’m sorry, Grandpa.

No voice splintered within the blaze. Get in the car.

Bile rose in Chris’s throat. His head swam. He wretched as his stomach convulsed. He fell forward, catching himself with his hands. His fingers dug into the cracked faux-leather seat, plunging into the spongy stuffing within.

The light disappeared. Slowly, Chris’s stomach settled, though his tongue still felt bloated in his sour mouth. The garage was quiet again, and he was the right height, so he pulled himself straight. The old car was empty except for plastic and fake leather. He closed the door.

As he went back into the house, he heard crying from the sitting room, and drifted toward it, hoping it wasn’t Harold or Lily or Marian wanting him to take sides.

Instead, it was his cousin Jim, red-eyed and clearly drunk from the vodka he’d been passing back and forth with his sister while they were supposed to be packing. He whimpered miserably, and his whole body was a pathetic whine, his shoulders hunched and his eyes welling. His face was slick with sweat from the summer heat. I hate being here.

Chris looked away. Jim had made him uncomfortable ever since the suicide attempt. He was the fragile one, and Pearl was the angry one, and Chris had an easier time with her because she never wanted anything from him.

How can you stand it? Jim’s eyes were pleading.

The air conditioning stuttered. Chris raised his shoulders in a tiny fraction of a shrug.

Jim chewed his bottom lip. He swayed unsteadily. Tears overflowed his bloodshot eyes, but his glazed look remained blank. Chris could remember when everyone had expected Jim to be the bright star of the family. He’d been the smart one, the one who was going to Georgetown and headed to law school, but that had been a long time ago. He worked a variety of service jobs now, which he couldn’t keep for more than a few months. He was late and absent and unreliable, but good at everything and nice to everyone, so he’d kept getting new chances, so far.

Humans are time travelers. Jim’s gaze wandered over Chris’s face.

Chris shifted uncomfortably. He hated it when people stared at him. It made him feel stupid.

We can’t stay in one timeline, people like us. People with trauma. All the bad things tunnel through. They tunnel through to each other. Do you know what I mean? A ragged breath caught him, forcing another sob. I’m so sick of traveling in time.

Chris coughed. Maybe you should lie down on the couch.

The couch? Jim’s eyes widened as if this were a new and startling idea.

Chris helped guide him to the threadbare sofa. It creaked as Jim lowered himself. Its flat cushions had once been overstuffed, but now, deflated, they clung to the hard, wooden frame. Jim murmured sleepily as he shifted into a fetal position, clinging to his knees and curling his head toward his chest.

When Chris looked up, he saw Pearl standing on the coffee table, ten years old and rickety with her t-shirt on backwards and a tangled nest of hair. She smacked her fist into the opposite palm and snarled.

From the direction of the couch where Jim was sleeping, no voice came, female and rough. What do you want me to say? I’m sorry?

Chris turned to see that Jim was gone. Birdie was sitting where he’d been. Her hair was gray and thin, but she looked much healthier than she had in the years after Grover died. Her skin was still mostly unmarked by liver spots. On her sweatshirt, an embroidered kitten peered out of a jack-o-lantern. She sat with her legs slightly apart, and her shoulders canted forward. The muscles in her face were taut.

Fine, Birdie didn’t say. I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I’m sorry! She clutched her heart and groaned. I’m a loathsome person! You’re the Queen of Everything! You’re always right! I’m a pile of shit! She dropped her hand and stared wide-eyed at Pearl. Is that okay, Your Highness?

You shouldn’t have said that to Jim!

Now, Jim was back, eight years old and sitting cross-legged on the carpet with his head dipped toward his chest.

Do you want me to lie to him? Fine. Fat kids have lots of friends, and losing weight won’t help you at all.

Just shut up! Pearl’s face turned red as she kicked the coffee table books and bowls of nuts onto the carpet. Cashews scattered everywhere. Birdie’s gaze turned to stone. She couldn’t stand wasted food.

Light leaked into Chris’s eyes as something approached from the hallway. They all turned their heads to see impossibly intense purple-blue-white pouring out of the archway.

No voice sounded like a match being struck. What the hell’s going on?

Birdie nodded sharply toward her husband. Grover, the kids are out of control.

Get their mothers.

Their mothers have decided to go shopping and leave us to babysit.

A pause. Well. A cough. Then. We’ll have to take care of it ourselves.

The light exploded. Burning blankness overwhelmed Chris’s vision and then began to consume his other senses. His face and hands went numb. He felt the painful pressure of something inside his throat, and then that feeling vanished, too. He was falling. Everything was gone but falling.

The light snapped back into nothingness like spent lightning, leaving Chris’s vision weird and dim.

Adult Jim was on the couch again. He made a soft, uneasy sound in his sleep. Everyone else was gone.

Chris rubbed his cold arms as he stared down the hallway. His skin felt stretched and thin. He felt like a spaghetti strand being pulled apart. He wanted to step backwards. Maybe sit in the rocking chair next to Jim. Maybe go back into the garage and hunch in a corner.

He tried to rock back on his heels, but his sense of balance was all wrong. He faltered forward. His orientation swung wildly as it had earlier, after he’d heard the knocking on the back bedroom door. Up became forward, and forward became down, until the hallway was a gaping maw beneath him.

He tripped over his feet, trying to stop himself from falling into the corridor. He stumbled into it anyway, banging his calf on the air conditioner, unable to stop. He grabbed at the knob of the linen closet, and clung there as if he were an astronaut desperately clutching an airlock door.

Holding on to the knob with one hand, he stretched across the hall, extending his other toward the bathroom door. His fingertips brushed metal. He couldn’t hold both knobs at once. He gulped a lungful of air and took the leap, releasing the linen cabinet, and fixing his hands around the bathroom doorknob an instant before he would have plummeted. He fought to open the door into a hallway that didn’t want to accept it, and shoved himself inside. The world righted itself. He locked the door behind him.

One of the lights was burned out, leaving the bathroom in a dingy pall that made the immaculate tile look shabby. His face stared back at him from the medicine cabinet, slightly rounded, with exhausted eyes.

His reflection didn’t say, Time travel is probably impossible. You’d have to violate the speed of light. Unless you believe thought is faster than the speed of light. It didn’t pause before continuing. Alternately, you could find a location of space-time collapse, such as that beyond the event horizon of a black hole.

Chris and his reflection had taken college physics together.

His reflection frowned sympathetically. You look tired.

Chris rubbed his forehead. He just needed to get past this. Past today. Past tomorrow. Past next month.

Time travel to the future is easy. All you have to do is wait. His reflection blinked at him. Are you going to go to the bathroom?

Chris walked away from the mirror, and into the little room that contained the toilet. He unbuckled to pee, and heard the approaching scuff of slippers against the tile. He heard the door to the toilet room open even though he hadn’t closed it. The fug of chemical roses stung the back of his throat.

Oh, you’re in here, no one said, standing close enough behind him that he could feel how her mass distorted space. Good, I won’t have to chase you down for bath time.

Chris’s stomach tightened. His skin felt sore and too small. There was no hand reaching for his, or pulling him out of the little room. His reflection stared at him pityingly.

There was the sound of a child screaming, and small hands and feet hitting the floor. No one said, Stop fighting. It’s just a bath.

Metal rings clanged on the rod as the flowered purple curtain slid aside. The faucet turned, and water startled out in bursts before settling into a stream. The knob turned again, and then again, until waves of steam were coming off of the water. Chris felt himself pushed to his knees by the side of the tub. His hand was tugged forward.

Is that hot enough?

Chris jolted and cried out as the water hit his fingers. He snatched them back, whimpering as he licked them.

Oh. Sorry. I didn’t realize how hot it was.

Someone else’s fingers prodded his painful skin.

You’re fine. I’ll turn it down.

The shower started, its hissing overlaying the absent voice.

Stay still. Little boys are disgusting. That’s what makes you boys, always running around, getting into things. I have to clean you everywhere. Will you stop? It’s just shampoo. Stay still.

The doorknob squeaked, starting to turn, but the lock arrested it partway. The door shook with the gentle rap of someone’s knuckles—a quiet, interrogating knock, polite and short.

Just a second, Grover, Birdie didn’t call. Let me rinse the soap out of his eye, and then I’ll get the door.

Chris squeezed his eyes shut. Blue-purple-white blared through his lids as it surged into the bathroom. There was no one shoving him, and he did not feel his shoulders smacking against the side of the tub. There was no sound of a buckle. Nothing forced open his throat. There was no pain. There was nothing sick in him. Beneath the noise of the shower, there were no words, no words at all, not disgusting, not stupid, not your fault, you made me do it, not any words, no words. There was only the varying intensity of the shower’s hiss as the pressure fluctuated, and the smack of water hitting porcelain, and the plastic rustling of the shower curtain in the billowing steam.

For a few seconds, Chris was nowhere. When he was back, the light was gone. He sat quaking by the edge of the bathtub until he was sure it wasn’t coming back. His hand shook as he reached to turn off the faucet. He stared at the water swirling downward.

The doorknob rattled again, still stymied by the lock. Chris turned toward it. His whole body shook as if he were feverish.

Damn it, I need to pee! Are you trying to make my bladder explode?

Staccato, angry slaps shook the door with an urgency that was obnoxious and emphatic, not polite at all. The breath Chris didn’t even know he was holding escaped his lungs. Sorry, Pearl.

Chris’s shaking slowed, but he remained unsteady as he got to his feet. His reflection was still staring at him, shaking its head slowly.

Chris untwisted the lock. He opened the door as Pearl leaned in to hammer on it again. She pulled upright and whisked inside. Sweat from the humidity slicked her bangs to her forehead.

Escaping? Me, too. Just wait there, and we can waste time together. I only have to pee.

She went behind the partition. Chris heard the stream of urine, followed by a big sigh of relief, and the squeak of a toilet paper roll. The flush continued as she came back and went to the sink.

Fuck I hate this room. I hate all the rooms.

I don’t like it here either.

No kidding. I see you on Facebook trying to sell yourself as a chill dude, but I remember the guy from high school who put his fist through the wall.

That was ten years ago.

The angry is still in you. You should let it out. I like angry Chris better than repressed Chris.

I’m not angry.

Keep trying to push it down if you want to, but it’s going to burst through eventually, like a geyser.

Chris didn’t like the subject. He folded his arms and looked away. Did they find the cameo?

Who cares?

Pearl slid onto the counter and leaned against the mirror, obscuring Chris’s maudlin reflection.

If you want to act like you’re not angry, you should come outside and have some weed with me. It’s no fun alone, and Jim’s asleep.

I helped him lie down, Chris said. He told me he’s sick of time traveling.

Pearl nodded. He read some stupid book on quantum physics. One of the ones that promises if you hope for a golden pony, the universe will deliver one to your door. He’s obsessing about the part that talks about traumatic events tunneling through time to connect to each other, blah, blah, various bullshit.

She snorted and rolled her eyes.

I say there’s no time travel, because if there ever is, I’m going to travel back in time and Grandfather Paradox this shit up, and then the whole universe will break down.

She scratched her fingers through her hair in exasperation.

Ugh. I just can’t. I have to smoke. You should come.

Chris shook his head. He couldn’t escape to the backyard. It was too far, and in the wrong direction.

Pearl jumped down from the counter. She patted her pockets, pulled out a lighter, nodded in satisfaction, and tucked it back in.

Your loss.

She went back through the door with a swagger. It swung loose behind her. Chris opened his mouth to call for her to close it, but it was already too late.

The world tumbled end over end again until he was falling into the hallway. He pitched into the wall with the photographs, knocking his father’s high school portrait to the floor. He tried to bend to pick it up, and only fell further as down changed direction again, forcing him into the branch of the hallway that led away from the master bedroom, toward the old children’s rooms.

As down finally returned to its place beneath his feet, Chris looked up to see his father beside him. He wore a beard that Chris recognized from looking at his own baby pictures. His father wiped tears off his cheeks before they could fall into the coarse, black hair.

He was looking in Chris’s direction, but didn’t seem to see him; his gaze was angled toward someone shorter. Oh, Nancy. Every time we come, it’s the same. I always end up crying.

His father began walking down the hallway. Chris matched his pace, and they went on together.

A cast appeared on his father’s arm. The only signature was Chris’s, written in clumsy, newly learned block letters. I’m so stupid.

His father grew the gut he had never been able to get rid of after turning forty. Birdie’s so much better now. Even Dad is, well, better.

He lowered his head into his hands. His peppery hair was beginning to salt. I should be able to deal with seeing my parents three times a year.

He looked up again, and the salt had overwhelmed the pepper. He straightened the black tie he’d worn to his father’s funeral. I haven’t even cried. It’s disgusting. There’s something wrong with me. He halted, and stared in Chris’s direction with searching eyes that were meant for someone else’s face. Nancy, what’s wrong with me?

He aged again, lean from losing weight after the divorce. They’d reached the door to the first of the two children’s bedrooms. Chris’s father regarded it blankly. They tried their best. Everyone tries their best.

He disappeared.

The door to the first bedroom was open now. Inside, Chris could see Lily and Marian going through linens. They were wearing the clothes they’d had on yesterday, casual t-shirts and jeans meant for working at home.

No women’s voices blended into each other.

There’s so much junk in here.

Don’t call it junk—it’s Mom’s.

You can have it then.

I have nowhere to put it.

You think I do?

Then they were both five-year-olds in matching jumpers, clutching hands as they stared in fear at the open door. A baby—Harold—lay still and silent behind them in his crib. One flinched and shrank away. The other squeezed the first’s hand. Neither of them whimpered softly to herself.

Chris released a shout of incoherent rage, and slammed his fist into the wall. It broke through the plaster. Dust rained on him. He shook his hand loose, fury only intensified by the pain in his knuckles. The air smelled like Christmas trees and hair dye and his disgusting high school cologne.

Pearl laughed. She was leaning against the opposite wall, sixteen years old, and wearing a military overstock coat despite being indoors. Hey there, bad boy! You get all the points. Everyone’s going to go berserk.

Chris opened his mouth to respond, and she pointed ahead of them to the final corner where the hallway turned in on itself. The second children’s bedroom was nestled there, a strangely shaped add-on with a sloped ceiling. During family visits, they’d put twin cots in there. Jim was supposed to use a sleeping bag on the floor, but Pearl had always pulled him into the cramped bed beside her where she could protect him.

Chris shook his head. He refused to look there. He would not look there. He turned away instead, and his gaze caught on the narrow window installed at eye-height on the exterior wall. The view outside changed as he stared at it. Figures bustled through the verdant lawn which was flourishing and overgrown in the humidity. Someone ran a mower. A sign appeared in the yard. A woman he didn’t recognize stood beside it with Marian, making notes on a tablet, and then reappeared with a succession of couples and families.

One of the families kept coming. The lawn was cut back to make room for new flowers and lawn furniture. It was dead. It was covered in snow. Toys and children’s bikes littered the new growth. Children he didn’t know grew from toddlers to teenagers.

The lawn was gone. Another house went up in its place. The house began crumbling. Grass and trees grew through cracked walls. There was a field, and then a forest, and then the waters of a new sea. The light of the expanding sun swallowed the earth. In the void of space, stars birthed and died.

Chris widened his stance, and braced against the wall. The final turn in the hallway was still behind him. Up and down were spinning, and he knew that soon he was going to fall, and he refused to fall, he would not fall.

No voice came from the window where his reflection was blurred against the backdrop of the ending universe. You can’t stay where you are. It’s impossible to maintain a steady orbit around a black hole.

Chris cringed. There were tears in his eyes.

His reflection did not continue, From outside, a black hole is too bright to see. It swallows light, but it also spits out a continuous stream of particles whose twins have fallen past the event horizon. The expelled radiation is too far into the ultraviolet spectrum for humans to see. The eye tries to make sense of it by comparing it to other colors. Blue. White. Purple. You see what I’m saying.

Chris’s throat constricted.

The reflection wavered. No one knows what it’s like inside a black hole. Information can’t escape. It’s literally impossible. No one can know what it’s like inside a black hole unless they’re inside one. His reflection did not pause, and it did not repeat, You see what I’m saying.

There was no polite knock on the door behind him. There was no voice pulsing like his heartbeat, echoing in his ears. Sick disgusting your fault if you weren’t so stupid shut up stop crying filthy you want this making me do it too stupid to be my grandson your mother is a slut disgusting disgusting be quiet.

Chris began shaking. Gravity broke his grip on the wall. He plunged blindly down the dead end behind him. His back smacked against the door.

His blood pressure surged. Throughout his life, he’d worried about what a stupid, bad person he was, how his temper flared and that was bad, and then he was silently withdrawn and that was bad, and sometimes his eyes went glassy and he disappeared and that was bad. He tried to keep himself contained, to seem calm and normal, but the anger always burst through. His teachers yelled at him, and he lost the first girlfriend he ever moved in with, and he cut off all his friendships a few months in, before they could realize how disgusting he was.

He was shaking so much that his body rattled against the door like knocking. His throat was dry and sore. He pressed his hands flat against the wood, and aching cold radiated into his palms.

Inside that room, there was a lamp that sat on the bookcase next to where they’d set up the cots. He’d stared at that lamp too many times, had lost himself in the stripes on its shade, trying to reduce himself to bars of white and yellow so that he could escape from badness, from filth, from being someone with a body.

He realized now that he knew how heavy that lamp was. He knew how it would feel in his hands to swing it. He knew how it would arc through the shadows toward his grandfather, and how his grandfather would turn away from the cot just before it hit and fix him with eyes like gravity wells. He knew how the lamp would crack against his grandfather’s head, and how the fractures would snake through the porcelain, and how his grandfather would cry out as he fell. He knew how the paradox would taste as it roared into the universe.

It was a beautiful, blooming promise of the future, and it was easy to travel to the future.

He turned to face the door, and shoved it open.

Buy the Book

Placed into Abyss (Mise en Abyse)

“Placed into Abyss (Mise en Abyse)” copyright © 2020 by Rachel Swirsky

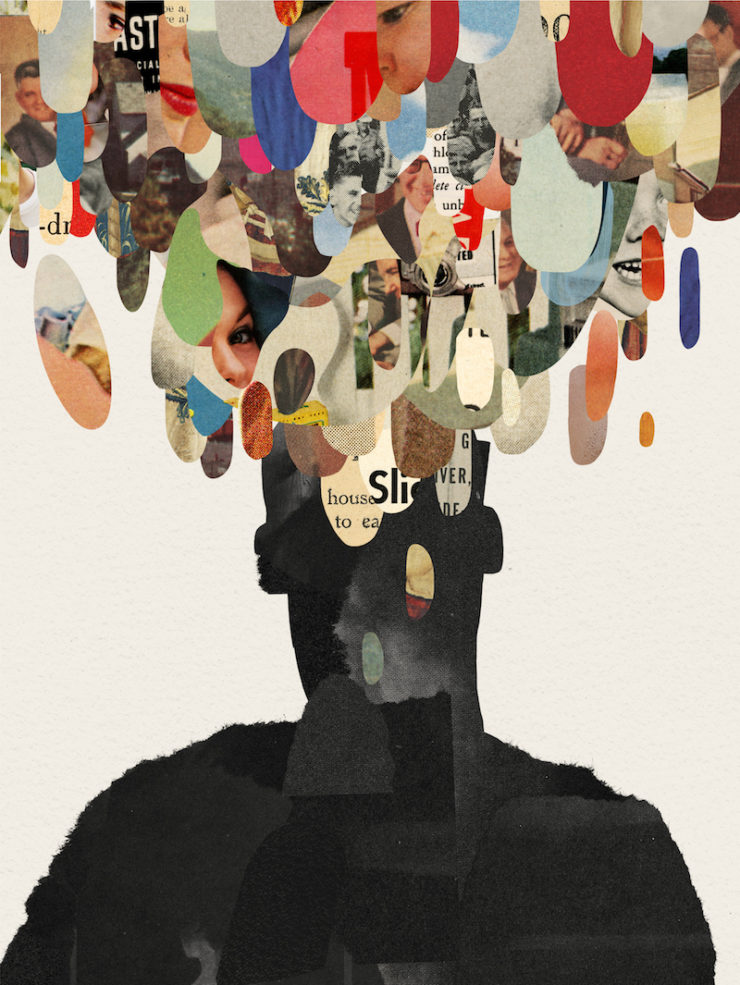

Art copyright © 2020 by Keith Negley